Evolution of protein interactomes across the tree of life

How does Darwinian evolution change molecular networks?

Large-scale protein interactome data reveal how protein-protein interaction networks change through evolution and how changes in these networks impact phenotypes and organismal response to environmental fluctuations.

The interactome network of protein-protein interactions captures the structure of molecular machinery and gives rise to a bewildering degree of life complexity. A critical property of interactomes is the resilience to protein failures as the breakdown of proteins affects the exchange of any biological information between proteins in a cell and may lead to cell death or disease.

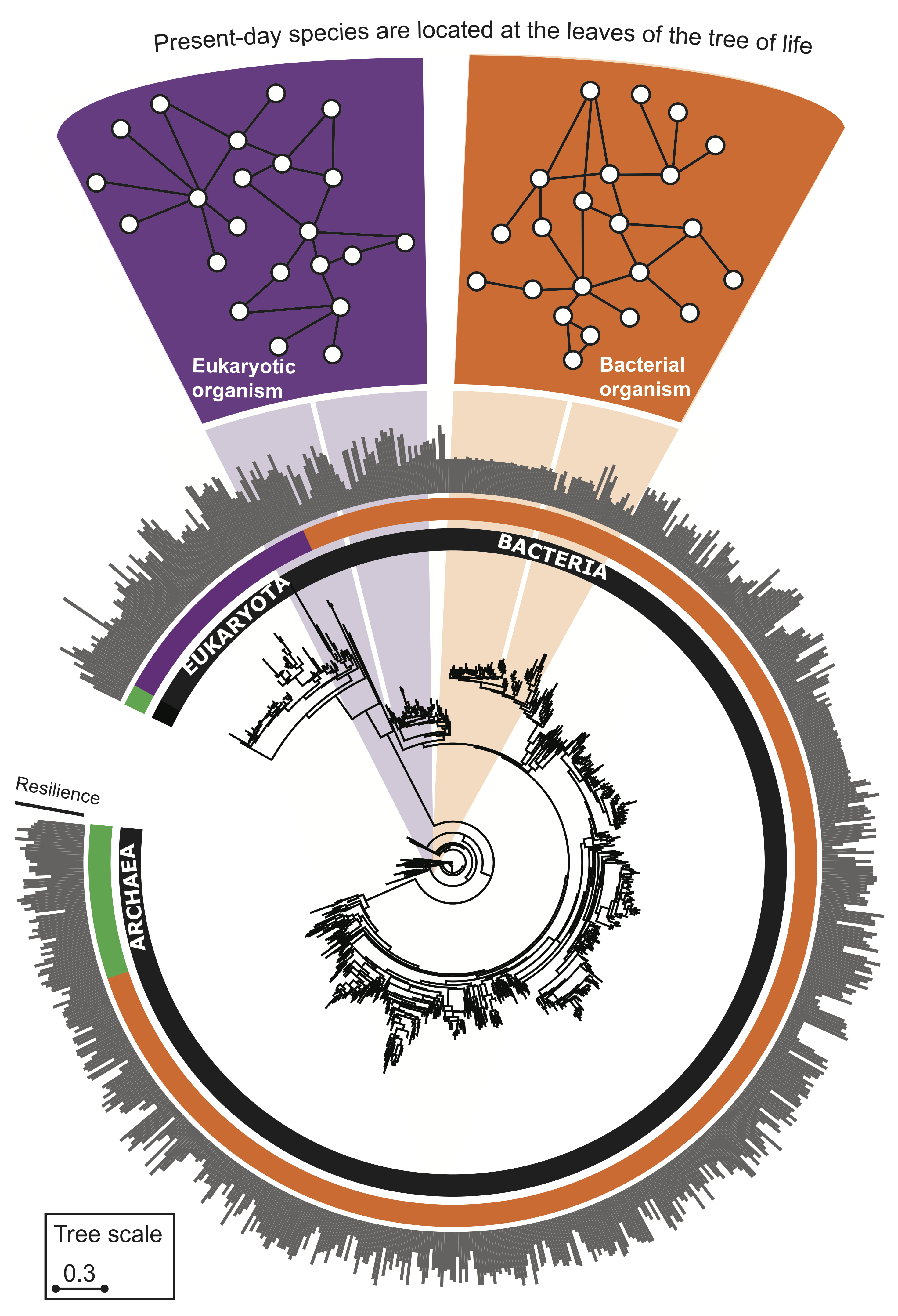

By studying interactomes from 1,840 species across the tree of life, we find that evolution leads to more resilient interactomes, providing evidence for a longstanding hypothesis that interactomes evolve favoring robustness against protein failures. We find that a highly resilient interactome has a beneficial impact on the organism's survival in complex, variable, and competitive habitats.

Answers to the question of PPI network evolution have implications for informing biology and answering numerous questions at the forefront of medicine, from interpreting genome-wide association data to drug target identification and drug discovery.

[Stanford News & Highlights]: New research shows that species evolve ways to backup life’s machinery

[Poster]: Evolution of resilience of protein interactomes across the tree of life

[Slides]: Invited talk at CEHG 2019

[Slides]: Spotlight presentation at ISMB/ECCB 2019

[Video]: Spotlight talk at ISMB/ECCB 2019

Protein interactomes across the tree of life

The following phylogenetic tree shows 1,539 bacteria, 111 archaea, and 190 eukarya. As ancestral species have gone extinct, older protein interactomes have been lost, and only interactomes of present-day species are available to us. For each species, we construct a separate PPI network, i.e., the protein interactome. An interactome captures all physical protein-protein interactions within one species, from direct biophysical protein-protein interactions to regulatory protein-DNA and metabolic interactions.

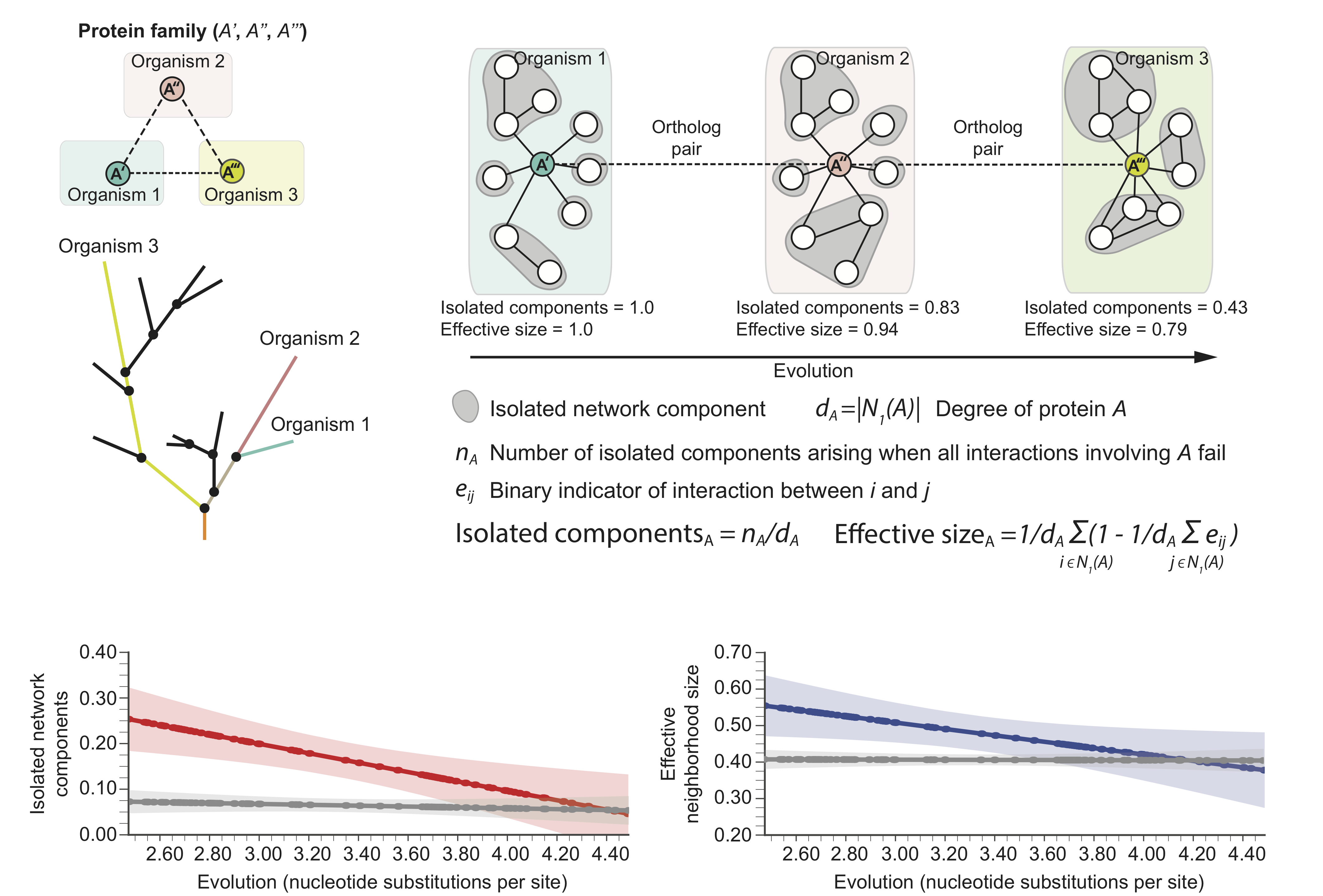

Evolution leads to more resilient interactomes

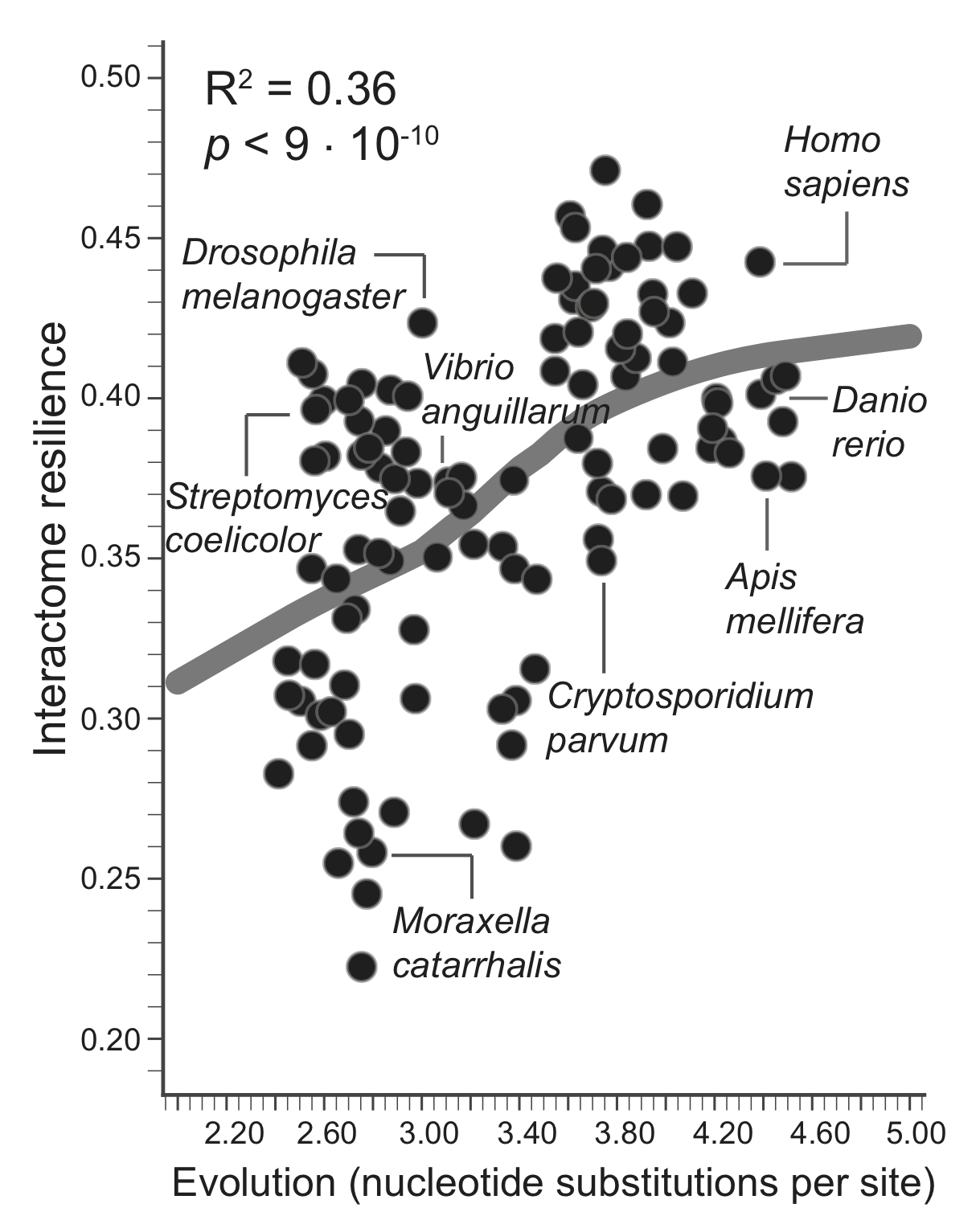

A greater amount of genetic change is associated with a more resilient interactome structure, which means that through evolution PPI networks are becoming more and more resilient to protein failures. A species that has undergone more genetic change has a more resilient interactome, giving empirical evidence for a longstanding hypothesis that interactomes evolve favoring robustness against failure of proteins.

The evolutionary time of a species, which is defined by the total branch length from the root to the leaf (nucleotide substitutions per site) representing that species in the tree of life, thus predicts resilience of the species' interactome, providing empirical evidence that interactome resilience is an evolvable property of organisms. Three species with the largest evolutionary time (far right on the x-axis) have on average 20.4% more resilient interactome than the three species with the shortest evolutionary time (far left on the x-axis).

A resilient interactome has an astonishingly beneficial impact on the organism's survival in complex, variable, and competitive habitats

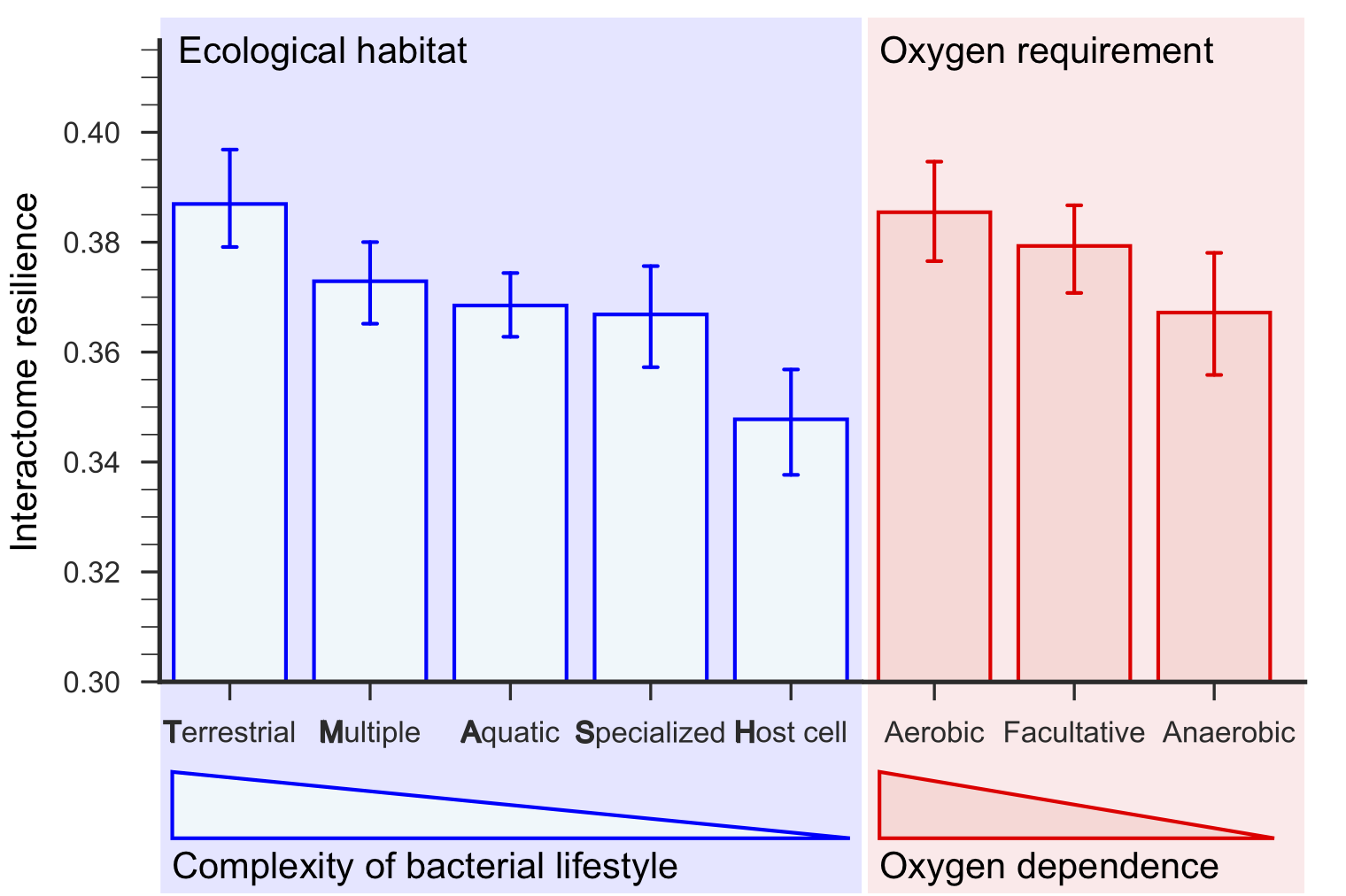

Species with highly resilient interactomes can survive in more diverse and competitive environments, as revealed by exceptionally strong effects between the resilience and the level of co-habitation and the environmental scope. Species with more resilient interactomes have also significantly more regulatory genes in their genomes, which indicates higher environmental variability of the species' habitats.

Terrestrial bacteria living in the most complex ecological habitats have the most resilient interactomes, and host-associated bacteria have the least resilient interactomes. Furthermore, interactome resilience is indicative of oxygen dependence; the most resilient interactomes are those of aerobic bacteria, followed by facultative and then anaerobic bacteria, which do not require oxygen for growth.

Evolution mitigates local network structural changes in protein interactomes

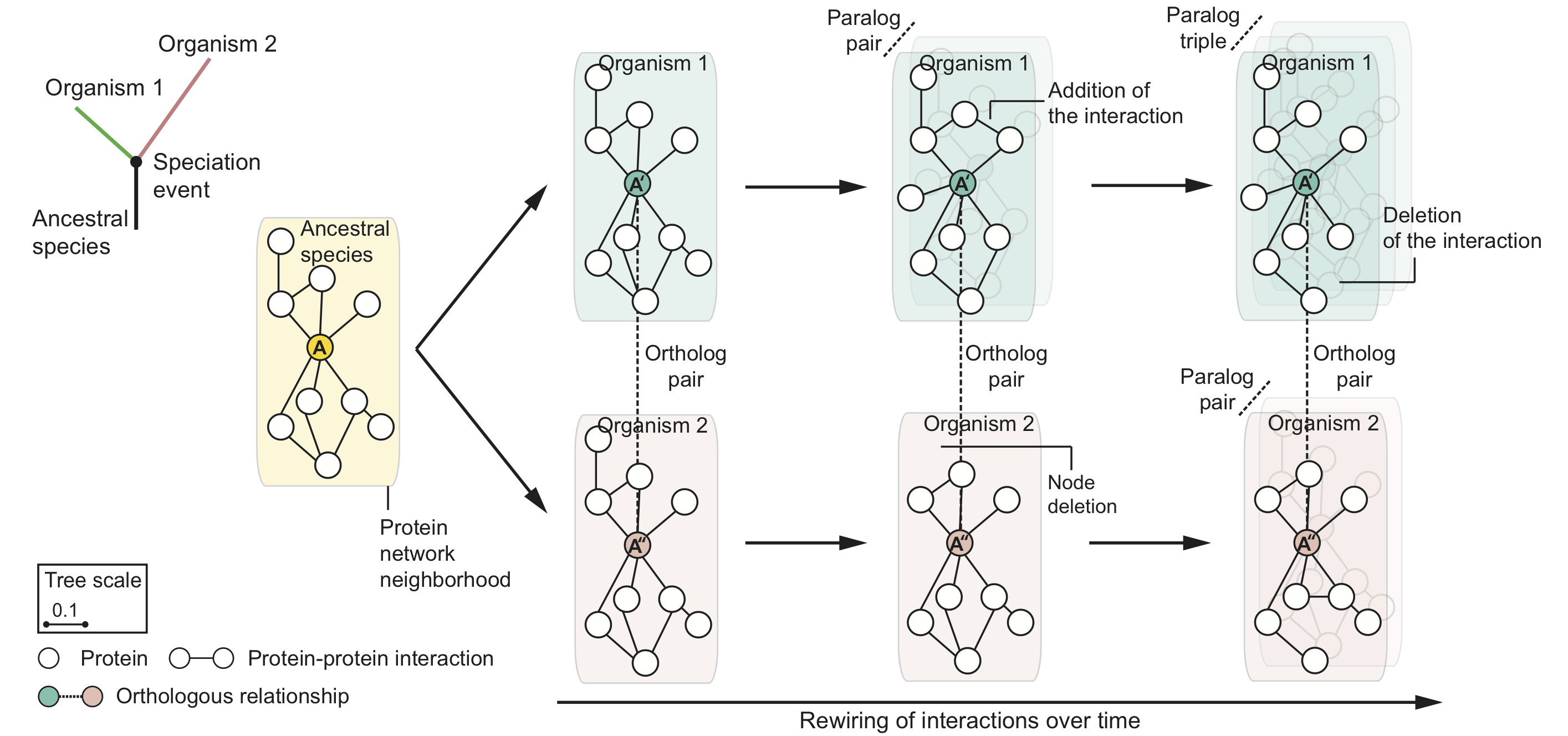

The following hypothetical phylogenetic tree illustrates a speciation event that gives rise to two lineages and leads to present-day organisms '1' (green) and '2' (pink). In this example, a single ancestral protein A that was present in the ancestral species gives rise to proteins A' and A'' upon speciation; A' and A'' form an orthologous protein pair. As the two newly arising species diverge and protein sequences evolve, local protein network neighborhoods in their interactomes can rewire independently over time. Shown are also in-paralogs, proteins which arise through gene duplication events in species '1' and '2' after speciation.

These structural changes in local protein neighborhoods suggest the following molecular network model of evolution: For orthologous proteins in two species, as the evolutionary distance between the species increases, the proteins' local network neighborhoods become increasingly different and the neighborhood becomes more interconnected in the species that has undergone more genetic change.